Mistakes often made by inexperienced event organizers

(this is geared toward events of size 50-5000, and probably a lot less useful for e.g. a casual gathering with 5-10 friends than e.g. a 100-person weekend conference.)

- do before anything else:

- goals, date, and venue. why figure out goals, pick a date, and pick a venue before all else?

- so many other tasks are blocked on those. try doing marketing for an event without knowing where/when/what/why it actually is!

- once you’ve figured those out, you’ve committed yourself in a way that will mentally prepare you for the fiddly details (i.e. the rest of this doc)

- figure out your goals, broadly speaking. for ex: write a one-pager, send it to a couple friends, think for 20-60 minutes

- this should be real, not fake — there’s a reason you’re doing this first. if you come out of it realizing that an event is the right thing to do, run an event; if not, don’t!

- leading questions:

- what do you want?

- seriously, what do you want?

- why are you running an event?

- what are other things you could do that would satisfy those goals? what about doing those other things instead?

- what reasons do you have to think that running an event would be more effective toward those goals than some other thing you could do?

- what are other things you could do that would satisfy those goals? what about doing those other things instead?

- what do you want the event to accomplish?

- why do you have those goals?

- why again?

- (ad infinitum)

- why again?

- how will you know whether you accomplished those goals?

- why do you have those goals?

- what do you want?

- pick a date. ask a few potential attendees if they have any conflicts. some common mistakes:

- don’t pick a date that coincides with another event that your attendees will want to go to. i once picked a date for an OPTIC forecasting tournament that was the same date as the putnam, and we lost ~ 15%-20% of possible attendees.

- try to avoid coinciding with national/religious holidays — many people schedule things on top of jewish holidays, which forces me to pick between being a good jew vs going to their awesome event.

- pick a date/time that generally works for the people you want to attract. e.g. don’t pick a weekday at 3pm for working folks, or a work event for jews on a saturday, or summertime for students.

- pick a venue.

- finding a good venue as early as possible in the process is so ridiculously important and so often undervalued. you do not want to be in the unfortunate position of having venue issues, you do not want to be scrambling to find a venue last-minute. this is one of the few things that can totally fuck up your event before it starts.

- (sidenote: if you’re considering running an event in the SF bay area, check out Lighthaven. i have literally never encountered a venue in which i would rather run an event — it’s stunningly beautiful, wonderful for parallel small-group conversations, incredibly customizable for different types of events, and about a hundred other things you want in a venue. strong recommend!)

- goals, date, and venue. why figure out goals, pick a date, and pick a venue before all else?

- food matters WAY more than you think it does

- why?

- people don’t enjoy themselves when they’re hungry. they’re cranky, they get more upset, they don’t have patience, etc.

- eating together is an incredibly bonding experience: to the extent that “bonding” is one of your central goals for the event, food is good at this, one of the most effective things you can do

-

from austin chen:

one of my favorite business books is “Never Eat Alone”. I’ve never read it but the title says it all

(I don’t think you should literally practice that but — yeah humans are like hardwired to like the people they share meals with)

ross rheingans-yoo responds:

Having read/listened to about 70% of it, I think the title doesn’t actually say all or even most of the content of the book, which has a large amount of “how to organize your social life as a systematizing autist / sociopath”.

That being said, the title is on its own a good thing to have in mind.

-

- in particular, many organizers realize that “food is important,” but don’t quite realize exactly how fucking important it is. i doubt you need convincing that food is important, but i hope i can just repeat it to you enough that you should make your food situation really really good

- in particular, consider spending:

- $10-$25 /person /meal, depending on e.g. how fancy you want to get, whether you’re doing buffet style or individually packed, etc

- 1/4-3/4 of the budget of your event on food

- in particular, consider spending:

- if you’re not serving food, strongly consider serving food

- if you’re serving poor-quality food, or small portions, strongly consider serving better quality food with bigger portions. food does cost money — consider shifting more of your budget to an actually-good food-experience, or feeling less bad about spending $x on food

- if you’re not quadruple checking that your food is coming on-time, that it’s high-quality, that it’s what you ordered & as much as you ordered, that it’s the right kind, that it’s as vegan/vegetarian/gluten-free/allergen-free/etc as you need it to be, that it’s hot/cold/whatever temperature you need it to be — strongly consider doing so

- serve good drinks

- serve good snacks in between meals

- probably err on the side of buying too much > too little

- don’t just think about the food itself, but all of the structures around the food:

- where you’re serving the food; how long it’ll be out for; what the lines look like; etc

- where people are eating the food; how long they’re eating it for; what sorts of groups will form, whether you can make the groups better by their own lights; etc

- remember to think about the things you actually care about! don’t just optimize for efficiency!

- 3-5mins of lines to get food might be a lot better than 0 mins — it gives people an opportunity to find folks in line with whom they can chat and (potentially) sit down to eat

- having people sit on the ground might be better than having formal tables — the ground is a little uncomfy, but encourages more natural groups to form + is easier to socialize

- downsides:

- food is quite expensive, sometimes the biggest line-item budget. it also scales linearly with the # of attendees, which can make planning hard

- food is pretty annoying to handle. there are a bunch of regulations, people can get sick, it has to be kept hot/cold, it goes bad quickly, etc.

- why?

- the one secret tip most conference organizers don’t want you to know: you don’t have to do the boring stuff. you can think carefully about the experience you want your attendees to have, then optimize around that.

-

misha glouberman’s post “Everything you did to make your conference better actually made it worse” is such a great post on this topic, with some great concrete examples.

Say you had 200 people in a room and you wanted to stop them from talking to each other. A great way to do this would be to give one of them a microphone and put the other 199 in chairs facing forward.

-

examples of boring stuff you can probably cut/refactor better:

- endless 1-on-1s

- talks from bad/boring speakers

- maybe just talks at all?

- “everyone go around and say your name, how you first heard about this event, and a fun fact”

- in general most icebreakers are fake. why are you doing it? what’s your goal here?

- okay, but like what’s your real goal here?

- sure, but if that wasn’t your goal, what would the goal actually be?

- okay, but like what’s your real goal here?

- in general most icebreakers are fake. why are you doing it? what’s your goal here?

- overly long intro/closing speeches. just get into the good stuff!

- panel discussions are often really hard to get right, and when they’re wrong they’re pretty bad

- scheduled breaks (can be good, but often executed poorly/leave a lot of value on the table)

- mandatory, contrived team-building exercises

- awards ceremonies that drag on with speeches for minor recognitions

-

examples of non-boring stuff:

- if you want attendees to make new friends, you can do stuff like speed-friending (thread on how to run this well)

- if you want attendees to learn some concrete skill, you can ask a practitioner of that concrete skill who’s demonstrated that they’re competent at teaching it extremely well (e.g. at previous events, or on YouTube/Twitch) to give a workshop

-

- you should be constantly modeling your attendees, constantly checking that model against reality (e.g. by asking your users), and constantly updating that model. some common mistakes:

- when you’re modeling an attendee, you should think of them as being mentally exhausted, physically tired, overworked, overstressed, overanxious, and

a bit of an idiotnot caring as much about your event as you, the organizer, does. they have vastly less context. they’re probably only the first 5. implications of this abound, see e.g. “don’t use a map” (below) or “make your signs like 5x bigger” (also below) - many people don’t really understand their preferences well at events. knowing peoples’ preferences better than they do is super useful. examples:

- people constantly complain about loud music at parties, but it fills an important social role (sewing together gaps in conversations, providing something to talk about, giving people an excuse to dance, breaking up big conversations into smaller conversations)

- at conferences, people often feel like they should go to a big talk, when really they should probably meet with people 1-on-1 or in smaller conversations.

- when you’re modeling an attendee, you should think of them as being mentally exhausted, physically tired, overworked, overstressed, overanxious, and

- small pushes on key coordination can go a long way.

-

austin chen:

probably the whole job of an organizer is to push on coordination, otherwise they wouldn’t need the event in the first place

-

examples:

- people will by-default just get dinner at a restaurant or something. if you do a tiny bit of coordination for them — like handing them a list of restaurants nearby, or making a channel in your slack/discord/whatever for “#dinner-plans” — you’ll unlock a lot of value. sometimes you can literally just round everyone up, shout “if you want thai food, go to this corner and meet all the other people getting thai food; if you want italian, go to that corner; if you want chinese, go to that corner” → let everyone go to the cuisine of their choice and make some new friends.

-

leila clark:

Oh this reminds me of one of my favourite unconference techniques which is to have people put ideas on a board and then have others gather around the things they want to do, then have them break out.

-

- having some sort of attendee database with contacts, emails, and how people can help them/how they can help others

- having some sort of central communication system, like a slack or discord or groupchat

- setting up default points where people can just hang out/cowork/vibe/eat/meet each other

- people will by-default just get dinner at a restaurant or something. if you do a tiny bit of coordination for them — like handing them a list of restaurants nearby, or making a channel in your slack/discord/whatever for “#dinner-plans” — you’ll unlock a lot of value. sometimes you can literally just round everyone up, shout “if you want thai food, go to this corner and meet all the other people getting thai food; if you want italian, go to that corner; if you want chinese, go to that corner” → let everyone go to the cuisine of their choice and make some new friends.

-

- people don’t know where anything is. people will never know where anything is, no matter what you do. but there are a few things you can do to prevent the worst of the worst:

-

don’t have a big map — this requires people to figure out where they are, where they want to go, and how to get from one place to another. that’s a lot!

- “are we the red star, or the yellow exclamation point…?”

- “which room was the talk in? 45b or 54d? or was it the Skyroom?”

- “do i go up the stairs and to the left? or do i have to take the elevator first? which one? to what floor?”

-

have a lot of signs that say very little on each sign, and place them EXACTLY where someone would be looking for them. examples:

-

when do you want to know where the bathroom is? when you’re walking into the venue, when you’re walking out of the venue, or when you’re walking out of any session space.

-

when do you want to know where lunch is? at like noonish: don’t put up signage telling people where lunch is until then

-

at intersections, or right before someone goes down a long hallway — it’s costly for them to make a decision about where to go, so having an answer right in front of them goes a long way

-

a lot of this comes down to modeling the attendee experience really, really well

-

joel becker (below quote is completely taken out of context, but IMO applies here):

you should be iterating + attempting to model attendees/getting better at this over time

-

-

make your signs like 5x bigger, with minimal info

-

bigger

- people hate having to squint at signs!

- i consistently see people think “that’s gotta be big enough, right?” → it’s not even close to big enough

- think HUGE signs with HUGE font

- bigger than what you’re currently thinking

- yup, still bigger

- okay that’s probably about right

- yup, still bigger

- bigger than what you’re currently thinking

-

minimal info

- model your attendees, try to figure out what they want when they’re about to look at your sign, then give them exactly the info they want and no more.

- like half of the things that people want to find are bathrooms and food. make these ones so ridiculously clear that i’d be difficult to avoid knowing where they are.

-

negative examples:

-

too much info, not nearly big enough:

-

-

right amount of info, but way too small, and still some distracting visual elements:

-

-

positive example:

- it’s HUGE, it’s exactly what the people need, they don’t need to think at all, it’s no additional info, it’s a chef’s kiss

-

but even if you print your sign HUGE with HUGE font and minimal info — people don’t read. they never read. expect this ahead of time, see “modelling an attendee well” above

-

joel becker, against this section:

i feel like i did absolutely none of this and everything was fine, because there are bigger wins elsewhere. (in particular people)

-

- premortem the whole event, many times, in every stage of the process, and for many sub-processes

- premortems are so fucking awesome. they’re just fantastic. i love them.

- i put the premortem guide that i use below:

- meta

- i’d recommend reading through the whole doc before actually doing one yourself

- i’d recommend writing your premortem out, and/or recording a conversation with your team

- first: imagine the event has just finished. close your eyes, really put yourself in that headspace.

- now imagine that things went…

- really, really badly. worst-case. shit hit the fan. pause for a moment.

- what happened?

- why did it go really badly? list as many scenarios as you can think of

- what factors led to those scenarios?

- what can you do to make those scenarios less likely to happen?

- what can you do to make those scenarios less bad if they were to happen?

- fine/okay/meh, but you lost a lot of potentially value. pause for a moment.

- what happened?

- why did it go really meh? list as many scenarios as you can think of

- what value wasn’t captured? why not?

- what can you do to capture make it more likely that you’ll capture that value?

- what can you do to make any value you do capture much better?

- really, really well. everything went smoothly, everyone had a great time. pause for a moment.

- what happened?

- why did it go really well? list as many scenarios as you can think of

- what factors led to those scenarios?

- what can you do to make those scenarios more likely to happen?

- what can you do to make those scenarios even better if they do happen?

- really, really badly. worst-case. shit hit the fan. pause for a moment.

- meta

- for the “produce solutions” part of premorteming, i found it useful to reference my notes on some methods ive used for producing solutions

- why are premortems useful?

- they push you to notice the things that you’ve been flinching from

- they give teams a space to talk about things that might’ve been uncomfortable or hard to talk about

- they let you pick up on things that are harder to pick up on otherwise

- they give you a record of things that you’re concerned about/eager to do more of

- they let you prioritize between how important different tasks are

- against:

- joel becker: “these reasons didn’t strike me as very useful. i’m like just be less anxious + put things into high prio vs low prio”

- austin chen: “I’ve never put that much stock in premortems either, sorry”

- take pictures

-

this is useful for stuff like advertising, social proof, doing posts on social media, etc

-

by default, you’ll probably take too few pictures, because it’s not viscerally intuitive while the event is going on why you’d want a bunch of pictures. take more!

-

probably take a quick video or two, but i usually don’t find them nearly so useful as good pics

- your phone is definitely sufficient, but having a good camera (and someone who knows how to use it) does make a difference

-

group photos are particularly good — they seem a little annoying when you’re doing them, but are typically the main picture you end up using anywhere

-

austin chen:

bonus points if you can get a photographer to come and bring their fancy camera. you can hire for this too ofc, but it’s great when you have photographers like Misha or Rachel in your community

-

- naming (h/t conflux)

- names are really sticky & costly to change. it’s important to at least not use a really really bad name, but also note that a really really good name can be substantially better

- positive example: “Manifest” is itself a word, is a pun on “manifold festival” (which is also descriptive of the thing), and is also coherently within the world of manifold

- positive example: “Mox” has a number of good connotations (e.g. “moxie,” or “mana rocks”), but also doesn’t specifically bring some particular thing to mind, which also means it doesn’t limit the organization to something

- this post is great, and this post is pretty good (including the comments, which add some nuance-via-disagreement). this post is also directionally correct, especially when considering writing your slogan.

- ask an LLM for feedback on your name — in particular, ask it for reasons it might not work/be bad

- austin chen: “fun fact, I was deciding between 3 names and Claude said like ‘Mox is obviously the best choice’”

- ask friends for thoughts on names you have, but don’t just give them a potential name and ask for thoughts — give them a list of names, then ask which they think are particularly good/bad and why.

- names are really sticky & costly to change. it’s important to at least not use a really really bad name, but also note that a really really good name can be substantially better

- relax, have fun, lean into it :) (h/t wrena)

-

quoted from wrena:

One of the biggest things I pay attention to while facilitating an event is to persistently keep in mind what the participants are thinking and feeling. Some questions I ask myself are:

As a participant…

- How socially accepted would I feel in this environment? Do I feel like I can speak up and contribute to conversations? Do I feel welcomed and included?

- Something I do as an organizer to get these questions to "yes":

- Try to have an easygoing and accepting demeanor.

- Talk with attendees during breaks, and try to connect with them on something their interested in, to build rapport.

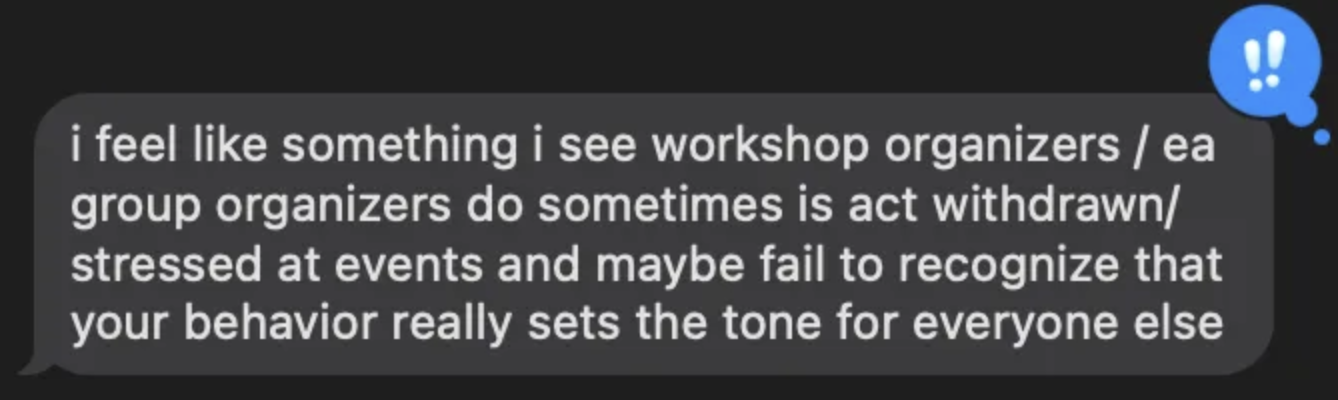

Some mistakes I made (and still make) in vibes:

- Acting visibly stressed and anxious.

- I was pretty anxious during my first few workshops. I now try to premortem what will make me stressed and reduce that before the workshop.

- I figured it was fine if I was acting high-strung because I associated "x person acting high-strung about an event" with "x person caring a lot about their work". But I think one of the main mental states to be in when presenting yourself to attendees as a group is being easygoing, accepting, and generally sort of chill, especially when people are already coming into something feeling anxious and wondering if they fit in. [Saul notes — Joe Carlsmith wrote an excellent piece on this topic, “On clinging.”]

- Note that in individual conversations, this is less applicable. [Saul notes — I disagree on this point.]

-

also from wrena:

-

concrete methods i use:

- picture someone you know who’s particularly charismatic, charming, social butterfly, outgoing person you know. try to act a bit more like them. (h/t nathan young)

- as wrena said, premortem things that you expect to cause you stress/anxiety explicitly to make it more likely that you won’t act stressed/anxious

- set up systems that will explicitly remind you to calm down (e.g. set a reminder on your phone, or set up a TAP that each time you walk through a particular doorway, you take a breath and release tension in your abs/shoulders/etc)

- (if legal) have half a beer

-

- i haven’t read “the art of gathering,” but most of the people who looked at drafts of this recommended i either read it or recommend it here. quick summary of the book here, full book here.

thanks to wrena sproat, jacob cohen, austin chen, joel becker, ross rheingans-yoo, leila clark, and a few others for thoughts & feedback.